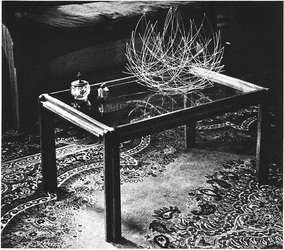

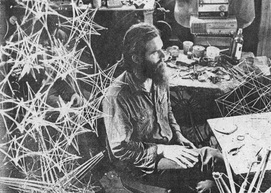

Background about Making Stars and Related Synergetic Compositions John Kostick in his workshop in Roxbury, MA, 1967

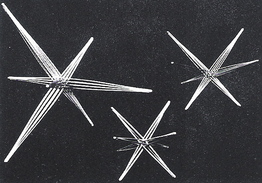

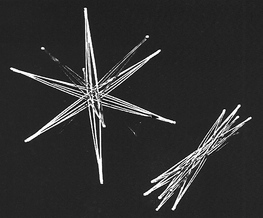

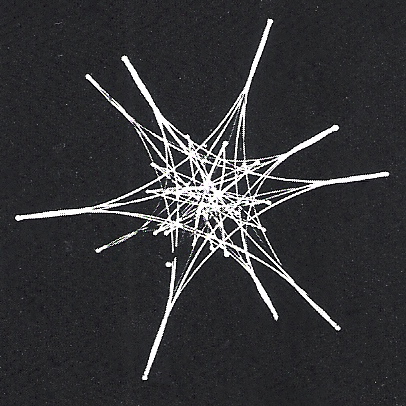

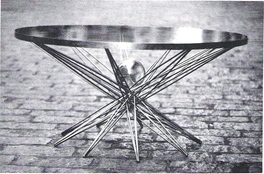

In 1962, while I was a Physics student at Brandeis, I attended a talk by Buckminster Fuller. I was impressed by his energy, and by how he had developed some geometrically-based, complex and sophisticated structures using simple components. The idea that stuck was that one could model and explore undiscovered spatial form and structure in a low-tech, hands-on way. A few years later, I began to do just this, starting with building models of some of the structures I had learned from Fuller. Of particular interest was a concept that he called Tensegrity, which is attributed to Kenneth Snelson. In these models, struts, or sticks, are suspended from each other by a network of tension members, such as strings, or wires. The sticks do not collide or intersect, but are coupled together by tension as they pass by each other. Thus symmetry and structural integrity are resultants of the assemblage of simple linear components, tension and compression, push and pull. The sparsity of this kind of definition of spatial form was very appealing to me. From the outset, the models I developed were rooted in this kind of mathematical conception, coupled with consideration of the physical properties of the components: The abstract lines that define geometric forms are indicated by actual parts aligned with forces that interact synergetically. There is an abstract aspect to these models, but there is an intrinsic physicality. Many of the synergetic structures that I discovered derive from the tensegrity concept. They can be seen as condensed, implicit tensegrity arrangements. This is perhaps most apparent in the magnetic puzzles. In these, an explicit tension network is replaced by the magnetic couplings, and the sticks are not suspended apart from each other, but are in contact as they bypass each other. In the stars, the tension networks are provided by deflection, by bending of the wires, or rods. From 1965 through 1971 I lived and worked in Roxbury, at that time a rundown district of Boston. I had a workshop/studio in a storefront, and together with a few friends formed a small company modestly called Omniversal Design. This revolved around developing the original designs that I was discovering into products that could be marketed through various venues. Some of these were furniture, table bases mostly, others were space frame systems. With our combination of skills and energies, we developed a variety of design objects in metal, that came to be referred to as stars. These stars are highly organized symmetrical compositions of simple parts. Some of these used curved silicon bronze and/or stainless steel wire, while others were composed of straight bronze rods. Some featured foldability, while others were more static. By 1968, the process of producing these stars was fully developed, and is substantially the same as we use today. The basic idea, the story of the stars, is that I found it inspiring that one could build objects that are mathematically elegant and have structural integrity, working with simple, readily available components, and using basic tools and techniques. These wire sculptures are stable, yet flexible, expressions of spatial symmetry that do not require any precision machining, casting, etc. The intent was, and still is, to make the geometry and physics that are expressed through the stars accessible and appealing. They are a kind of fusion of science and art. The development of handmade, original design products intended to be affordable was very much in and of the spirit of the times. The stars represented a new way to look at spatial composition, at how elements of structure can be organized. I found it rewarding to make and sell these novel objects with math and science content, expressed through handiwork and artisan skills. My focus, in general, is on mathematically interesting forms and innovative and effective ways to build them. In some cases this translates into utilitarian structures, in other cases making sculptural renditions of the patterns that I discovered. It should be said that while I did discover, and in fact was granted a patent on the use of some of these basic patterns, (U.S. Patent no. 3,546,049, 1970) a few others have independently discovered some of the same designs, notably Akio Hizume from Japan. I feel that this actually speaks to the veracity of the designs; they have a mathematical basis that is there to be discovered. I think of the objects that I make as conveying this content in an aesthetic and interactive way. I like to think of these stars as mathematical truths that you can hold in your hand. |

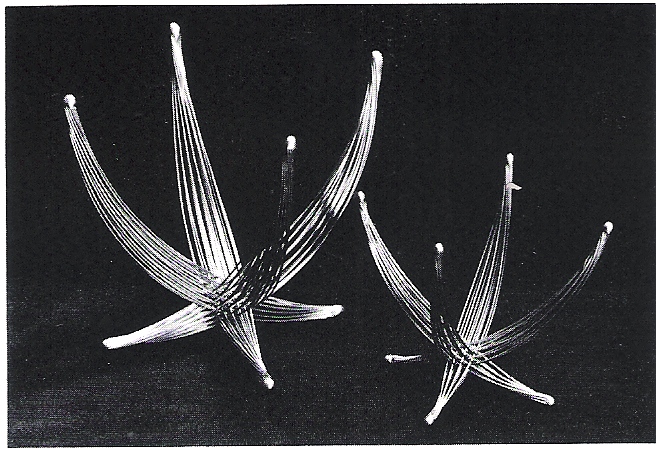

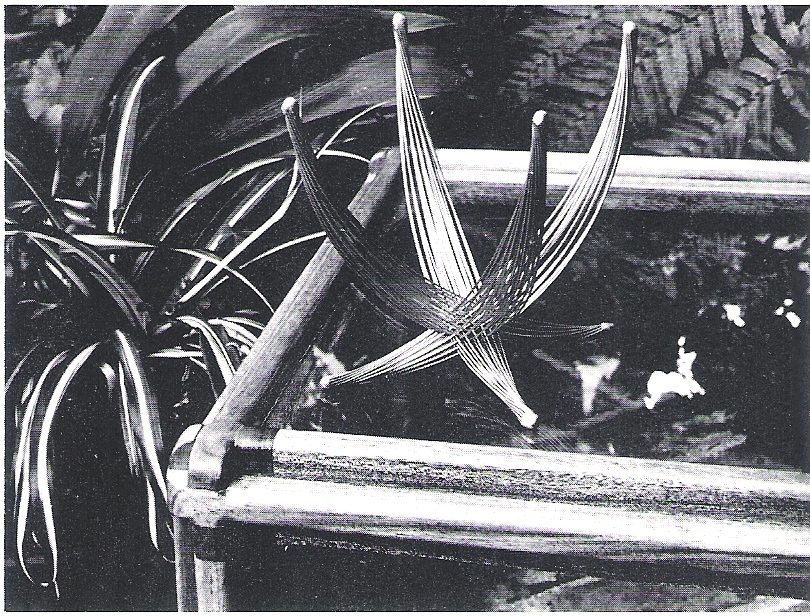

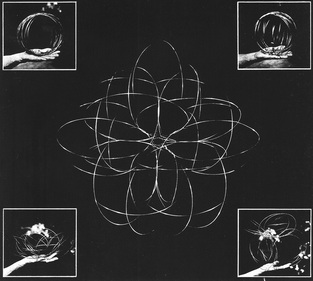

Photos of original work from the 1960s

(click on an image to enlarge it) |

Some Starring Roles

In the early 1970s CBS purchased a 16-Axis Star for use in the opening of CBS Playhouse 90, a short-lived remake of the television anthology series from over a decade earlier. The same footage was later used in the 1973 film The Conflict, starring Trevor Howard and Martin Sheen: |

|

In 1997, a Six-Axis Star made its way to being a prominent prop on the MIT math professor's desk in the movie Good Will Hunting: 8-year-old James demonstrating some foldable bronze stars: |